6 Language

Symbols

In the preceding chapter we discussed the

development of technoeconomic

organization and the establishment of

social machinery closely connected

with the evolution of

techniques. Here I propose to consider the evolution

of a fact that

emerged together with Homo sapiens in the development of

anthropoids:

the capacity to express thought in material

symbols. Countless

studies have been devoted to, respectively,

figurative art and writing,

but the links between them are often ill

defined. It has therefore occurred

to me that there might be some

profit in attempting to analyze those links

within a general

perspective. In part III we shall consider the aesthetic

aspects of

rhythms and values, but here, as we near the end of a long

reflection

principally concerned with the material essence of humans,

it may be useful

to consider how the system that provides human

society with the means of

permanently preserving the fruits of

individual and collective thought

came slowly into

being.

The Birth of Graphism

There

is a most important fact to be learned from the very earliest

graphic

signs. In chapters 2 and 3 we saw that the bipolar technicity

of many vertebrates

culminated in anthropoids in the forming of two

functional pairs (hand/tools,

face/ language), making the motor

function of the hand and of the face

the decisive factor in the

process of modeling of thought into instruments

of material action,

on the one hand, and into sound symbols, on the other.

The emergence

of graphic signs at the end of the Palaeoanthropians'

reign

presupposes the establishment of a new relationship between the

two operating

poles--a relationship exclusively characteristic of

humanity in the narrow

sense, that is to say, one that meets the

requirements of mental symbolization

to the same extent as today. In

this new relationship the sense

188

of

vision holds the dominant place in the pairs

"face/reading"

and "hand/graphic sign." This

relationship is indeed exclusively

human: While it can at a pinch be

claimed that tools are not unknown to

some animal species and that

language merely represents the step after

the vocal signals of the

animal world, nothing comparable to the writing

and reading of

symbols existed before the dawn of Homo sapiens We can therefore

say

that while motor function determines expression in the techniques

and

language of all anthropoids, in the figurative language of the

most recent

anthropoids reflection determines

graphism.

The earliest traces date back to the end of the

Mousterian period and become

plentiful in the Chatelperronian, toward

35,000 B.C. They appear simultaneously

with dyes (ocher and

manganese) and with objects of adornment. They take

the form of tight

curves or series of lines engraved in bone or stone,

small

equidistant incisions that provide evidence of figurative

representation

moving away from the concretely figurative and proof

of the earliest rhythmic

manifestations. No meaning can be attached

to the very flimsy pieces of

evidence available to us (figure

82).  They have been interpreted as "hunt

tallies," a form of

account keeping, but there is no substantial proof

in the past or

present to support this hypothesis. The only comparison

that might

possibly be drawn is with the Australian churingas, stone or

wood

tablets engraved with abstract designs (spirals, straight lines,

and

clusters of dots) and representing the body of the mystic

ancestor or the

places where the myth unfolds (figure 83). Two

aspects of the churinga

seem relevant to the interpretation of

Paleolithic "hunting tallies":

first, the abstract nature

of the representation, which, as we shall see,

is also characteristic

of the oldest known art, and, second, the fact that

the churinga

concretizes an incantatory recitation and serves as its

supporting

medium, the officiating priest touching the figures with

the tips of his

fingers as he recites the words. Thus the churinga

draws upon two sources

of expression, that of verbal (rhythmic)

motricity and that of graphism

swept along by the same rhythmic

process. Of course my argument is not

that Upper Paleolithic

incisions and Australian churingas are one and the

same thing, but

only that among the possible interpretations, that of a

rhythmic

system of an incantatory or declamatory nature may be

envisaged.

They have been interpreted as "hunt

tallies," a form of

account keeping, but there is no substantial proof

in the past or

present to support this hypothesis. The only comparison

that might

possibly be drawn is with the Australian churingas, stone or

wood

tablets engraved with abstract designs (spirals, straight lines,

and

clusters of dots) and representing the body of the mystic

ancestor or the

places where the myth unfolds (figure 83). Two

aspects of the churinga

seem relevant to the interpretation of

Paleolithic "hunting tallies":

first, the abstract nature

of the representation, which, as we shall see,

is also characteristic

of the oldest known art, and, second, the fact that

the churinga

concretizes an incantatory recitation and serves as its

supporting

medium, the officiating priest touching the figures with

the tips of his

fingers as he recites the words. Thus the churinga

draws upon two sources

of expression, that of verbal (rhythmic)

motricity and that of graphism

swept along by the same rhythmic

process. Of course my argument is not

that Upper Paleolithic

incisions and Australian churingas are one and the

same thing, but

only that among the possible interpretations, that of a

rhythmic

system of an incantatory or declamatory nature may be

envisaged.

If there is one point of which we may be

absolutely sure, it is that graphism

did not begin with naive

representations of reality but with abstraction.

The discovery of

prehistoric art in the late nineteenth century raised

the issue of a

"naive" state, an art by which humans

supposedly

represented what they saw as a result of a kind of

aesthetic triggering

effect. It was soon realized near the beginning

of this century that this

view was mistaken and that

magical-religious concerns were responsible

for the figurative art of

the Cenozoic Era, as indeed they are for all

art except in a few

rare

189

83

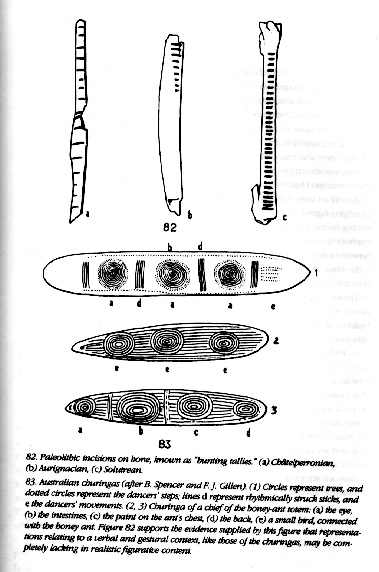

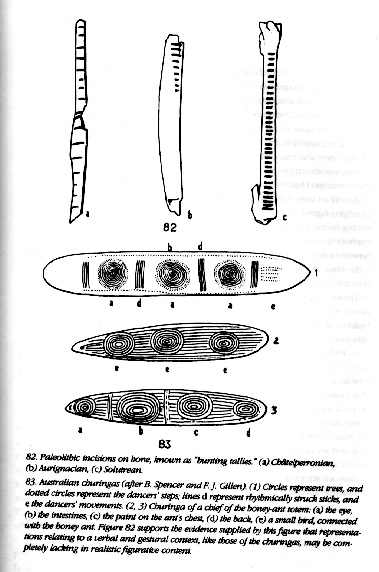

82. Paleolithic

inasions on bone, known as "hunting tallies."

(a)

Chatellperronian, (b)Aurignacian, (c) Solutrean. 83.. Australian

churingas

(after B. Spencer and F. J. Gillen). (1) Circles represent

trees, and dotted

circles represent the cancers' steps; lines d

represent rhythmically struck

sticks, and e the cancers'

movements. (2, 3) Churinga of a chief of the

honey-ant totem: (a) the

eye, (b) the intestines, (c) the paint on the

ant's chest, (d) the

back, (e) a small bird, connected with the honey ant.

Figure 82

supports the evidence supplied by this figure that

representations

relating to a verbal and gestural context, like those

of the churingas,

may be completely lacking in realistic figurative

content.

190

periods of

advanced cultural maturity. However, it was discovered more

recently

that the Magdalenian records on which the idea of Paleolithic

realism

is based were produced at what was already a very late stage

of

figurative art: They date to between 11,000 and 8000 B.C., whereas

the

true beginning belongs to before 30,000. A fact of particular

relevance

in our present context is that graphism certainly did not

start by reproducing

reality in a slavishly photographic manner. On

the contrary, we see it

develop over the space of some ten thousand

years from signs which, it

would appear, initially expressed rhythms

rather than forms. The first

forms, confined to a few stereotyped

figures in which only a few conventional

details allow us to hazard

to identify an animal, did not appear until

around 30,000 B.C. All

this suggests that in its origins figurative art

was directly linked

with language and was much closer to writing (in the

broadest sense)

than to what we understand by a work of art. It was

symbolic

transposition, not copying of reality; in other words, the

distance that

lies between a drawing in which a group agrees to

recognize a bison and

the bison itself is the same as the distance

between a word and a tool.

In both signs and words, abstraction

reflects a gradual adaptation of the

motor system of expression to

more and more subtly differentiated promptings

of the brain. The

earliest known paintings do not represent a hunt, a dying

animal, or

a touching family scene, they are graphic building blocks without

any

descriptive binder, the support medium of an irretrievably lost

oral

context.

Prehistoric art records are very numerous,

and statistical processing of

a large mass of data whose

chronological order is more or less definitely

established enables us

to unravel, if not to decipher, the general meaning

of what is

represented. The thousand variations of prehistoric art revolve

round

what is probably a mythological scene in which images of animals

and

representations of men and women confront and complement each

other.

The animals appear to form a couple in which the bison is

contrasted with

the horse, while the human beings are identified by

symbols that are highly

abstract figurative representations of sexual

characteristics (figure 91

and part II, figure 143). Having arrived

at such a definition of the content

of prehistoric art, we are in a

far better position to understand the connection

between abstraction

and the earliest graphic symbols.

The Early

Development of Graphism

Rhythmic series of lines or

dots continued to be produced until the end

of the Upper

Paleolithic. Parallel with these, the first figures begin

to appear

in the Aurignacian period about 30,000 B.C. They are, to date,

the

oldest works of art in the whole

191

of human

history, and we are surprised to discover that their content

implies

a conventionality inconceivable without concepts already

highly organized

by language. The content then is already very

complex, but the execution

is skill rudimentary: In the best samples,

animal heads and sexual symbols-already

highly stylized-are

superimposed on one another pell-mell.

During the next

(Gravettian) stage, toward 20,000 B.C., the figures become

more

deliberately organized. Animals are rendered by the outline of

their

cervicodorsal curve with the addition of details characteristic

of particular

species (bison's horns, mammoth's trunk, horse's mane,

etc.). The content

of the groups of figures remains the same as

before, but it is more skillfully

expressed. In the Solutrean period,

toward 15,000 B.C., engravers or painters

are in full possession of

their technical resources, which barely differ

from those of

engravers or painters of today. The meaning of the figures

has not

changed, and the walls or decorated slabs show countless

variations

on the theme of two animals and of a man and a

woman. However, a curious

development has taken place: The

representations of human beings seem to

have lost all their realist/c

character and are now oriented toward the

triangles, rectangles, and

rows of lines or dots with which the walls of

Lascaux, for example,

are covered. The animals, on the other hand, are

developing little by

little toward realism of form and movement, although-for

all that may

have been said and written about the realism of the animals

of

Lascaux-in the Solutrean they are still far from achieving such

realism.

In technical skill and mythological content these figures

are indeed products

of the "Paleolithic Middle Ages," but

it would be an error to

compare these groups of works to the frescoes

of our medieval basilicas

or to easel paintings. They are really

"mythograms," closer to

ideograms than to pictograms and

closer to pictograms than to descriptive

art.

So far as

human figures are concerned, the Magdalenian between 11,000 and

8000

B.C.-the period of the great series of cave paintings of Altamira

and

Niaux- sometimes exhibits a still closer connection with the

ideogram

and at other times a categorical return to realist/c

representation. As

for the animals, they are swept along on a current

in which the artist's

skill will eventually (at the time of Altamira)

result in a certain academism

of form and later, shortly before the

end of the period, to a mannered

realism that renders movement and

form with photographic precision. The

art of this later period was

the first to become known, thus giving rise

to the idea of primitive

or "naive" realism.

Paleolithic art, with its

enormously long time frame and its abundant records,

provides

evidence that is irreplaceable for understanding the real nature

of

artistic figurative representation and of writing: What appear to

be

two divergent tracks start

192

ing at the

birth of the agricultural economy in reality form only one.

It is

extreme! curious to find that symbolic expression achieves its

highest

level soon after its earliest beginnings in the Aurignacian

(figures 84

to 87).  We see art split away from writing, as it were,

and follow a trajectory

that, starting in abstraction, gradually

establishes conventions of form

and movement and then, at the end of

the curve, achieves realism and eventually

collapses. The development

of the arts in historic times has so often followed

the same course

that we are forced to recognize the existence of a general

tendency

or cycle of maturation-and also to recognize that abstraction

is

indeed the source of graphic expression. The question of the

return

of the arts to abstraction on a newly rethought basis will be

discussed

in chapter 14, where we shall see that the search for pure

rhythmicity,

for the nonfigurative in modern art and poetry (born as

it was of the contemplation

of the errs of living primitive peoples),

represents a regressive escape

into the haven of primitive reactions

as much as it does a new departure.

We see art split away from writing, as it were,

and follow a trajectory

that, starting in abstraction, gradually

establishes conventions of form

and movement and then, at the end of

the curve, achieves realism and eventually

collapses. The development

of the arts in historic times has so often followed

the same course

that we are forced to recognize the existence of a general

tendency

or cycle of maturation-and also to recognize that abstraction

is

indeed the source of graphic expression. The question of the

return

of the arts to abstraction on a newly rethought basis will be

discussed

in chapter 14, where we shall see that the search for pure

rhythmicity,

for the nonfigurative in modern art and poetry (born as

it was of the contemplation

of the errs of living primitive peoples),

represents a regressive escape

into the haven of primitive reactions

as much as it does a new departure.

The Spread of

Symbols

As we just saw, figurative art is inseparable

from language and proceeds

from the pairing of phonation with graphic

expression. Therefore the object

of phonation and graphic expression

obviously was the same from the very

outset. A part-perhaps the most

important part-of figurative art is accounted

for by what, for want

of a better word, I propose to call

"picto-ideography."

Four thousand years of linear writing

have accustomed us to separating

art from writing, so a real effort

of abstraction has to be made before,

with the help of all the works

of ethnography written in the past fifty

years, we can recapture the

figurative attitude that was and skill is shared

by all peoples

excluded from phonetization and especially from linear

writing

The linguists who studied the origins of writing

often applied a mentality

born of the practice of writing to the

consideration of pictograms. It

is interesting to note that the only

true "pictograms" we know

are of recent origin and that

most of them resulted from contacts between

ethnic groups without any

writing with travelers or colonizers from countries

with writing

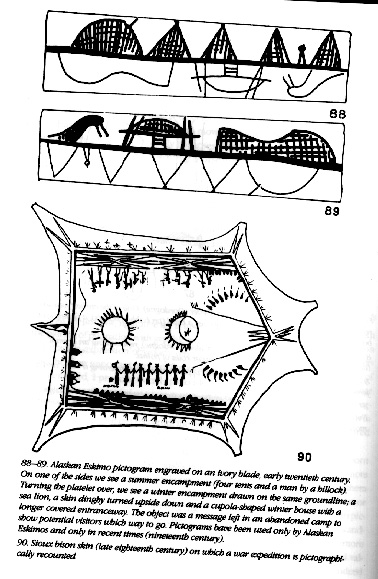

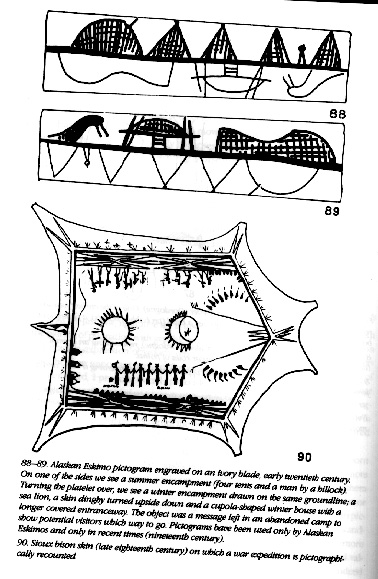

(figures 88 to 90):  Eskimo or Amerindian pictograms are therefore

not

suitable terms of comparison for acquiring an understanding of

the

ideograms of peoples who lived before writing was

invented. Furthermore

the origins of writing have often been linked

to the memorization of numerical

values (regular notches, knotted

ropes, etc.). While alphabetic linearization

may indeed have been

related from the start to numbering devices which

of necessity were

lin-

Eskimo or Amerindian pictograms are therefore

not

suitable terms of comparison for acquiring an understanding of

the

ideograms of peoples who lived before writing was

invented. Furthermore

the origins of writing have often been linked

to the memorization of numerical

values (regular notches, knotted

ropes, etc.). While alphabetic linearization

may indeed have been

related from the start to numbering devices which

of necessity were

lin-

195

ear, the same is not true of the

earliest figurative symboism. That is

why I am inclined to consider

pictography as something other than writing

in its

"infancy."

Through an increasingly precise

process of analysis, human thought is capable

of abstracting symbols

from reality. These symbols constitute the world

of language which

parallels the real world and provides us with our means

of coming to

grips with reality. By the time of the Upper Paleolithic,

reflective

thought-which had found concrete expression, probably from the

very

start, in the vocal language and mimicry of the anthropoids-was

capable

of representation, so humans could now express themselves

beyond the immediate

present. Two languages, both springing from the

same source, came into

existence at the two poles of the operating

field- the language of hearing,

which is linked with the development

of the sound-coordinating areas, and

the language of sight, which in

turn is connected with the development

of the gesture-coordinating

areas, the gestures being translated into graphic

symbols. If this is

so, it explains why the earliest known graphic signs

are stark

expressions of rhythmic values. Be that as it may, graphic

symbolism

enjoys some independence from phonetic language because its

content adds

further dimensions to what phonetic language can only

express in the dimension

of time. The invention of writing, through

the device of linearity, completely

subordinated graphic to phonetic

expression, but even today the relationship

between language and

graphic expression is one of coordination rather

than

subordination. An image possesses a dimensional freedom which

writing must

always lack. It can trigger the verbal process that

culminates in the recital

of a myth, but it is not attached to that

process; its context disappears

with the narrator. This explains the

profuse spread of symbols in systems

without linear writing. Many

authors of works on primitive Chinese culture,

Australian aborigines,

North American Indians, or certain peoples of Black

Africa speak of

their mythological way of thinking in which the world order

is

integrated in an extraordinarily rich system of symbolic

relationships.

A number of these authors mention the very rich

systems of graphic representation

available to the peoples they

observed. In each case, except perhaps that

of the early Chinese

where the records postdate the invention of writing,

the groups of

figures represented are coordinated in accordance with a

system that

is completely foreign to linear organization and consequently

to any

possibility of continuous phonetization. The contents of the

figures

of Paleolithic art, the art of the African Dogons, and the

bark paintings

of Australian aborigines are, as it were, at the same

remove from linear

notation as myth is from historical

narration. Indeed in primitive societies

mythology and

multidimensional graphism usually coincide. If I had the

courage to

use words

196

in their strict sense, I would be

tempted to counterbalance "mytho-logy"--a

multidimensional

construct based upon the verbal--with "mytho-graphy,"

its

strict counterpart based upon the manual.

The forms of

thought that existed during the longest period in the evolution

of

Homo sapiens seem strange to us today although they continue to

underlie

a significant part of human behavior. Our life is molded by

the practice

of a language whose sounds are recorded in an associated

system of writing:

A mode of expression in which the graphic

representation of thought is

radial is today practically

inconceivable. One of the most striking features

of Paleolithic art

is the manner in which the figures on the cave walls

are organized

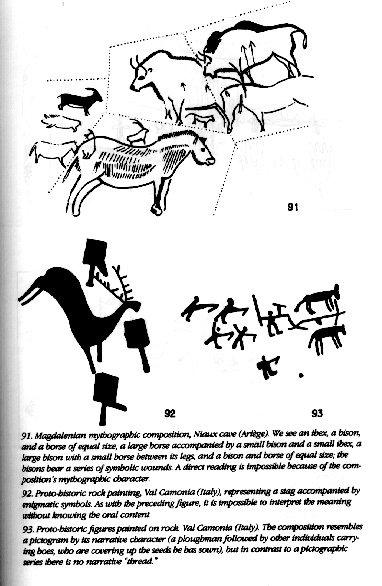

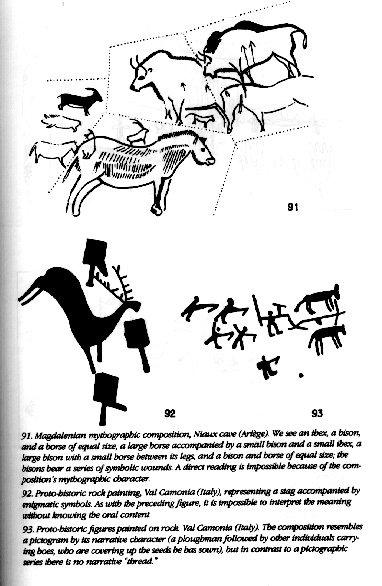

(figure 91).  The number of animal species represented is

small, and

their topographic relationships constant: Bison and horse occupy

the

center of the panel, ibex and deer form a frame round them at the

edges,

lion and rhinoceros are situated on the periphery. The same

theme may be

repeated several times in the same cave and recurs in

identical form, although

with variations, from one cave to

another. What we have here therefore

is not the haphazard

representation of animals hunted, nor "writing,"

nor

"imagery." Behind the symbolic assemblage of figures

there

must have been an oral context with which the symbolic

assemblage was associated

and whose values it reproduced in space

(figures 92 and 93). The same fact

is evident in the spiral figures

Australian aborigines draw on sand as

symbolic expressions of the

unfolding of their myths of the lizard or the

honey ant, or in the

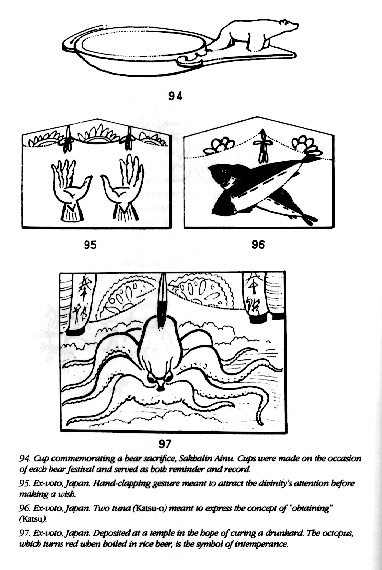

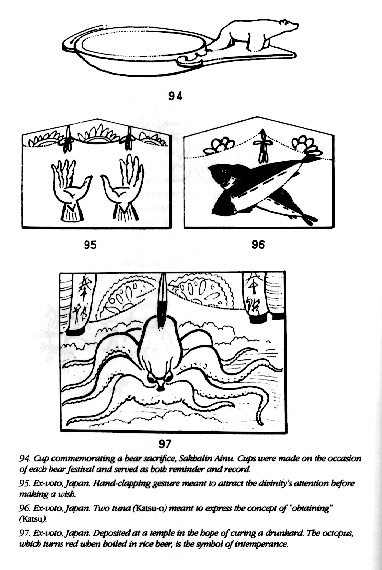

carved wooden bowls of the Ainus that give material

expression to the

mythified narration of their sacrifice of the bear

(figure

94).

The number of animal species represented is

small, and

their topographic relationships constant: Bison and horse occupy

the

center of the panel, ibex and deer form a frame round them at the

edges,

lion and rhinoceros are situated on the periphery. The same

theme may be

repeated several times in the same cave and recurs in

identical form, although

with variations, from one cave to

another. What we have here therefore

is not the haphazard

representation of animals hunted, nor "writing,"

nor

"imagery." Behind the symbolic assemblage of figures

there

must have been an oral context with which the symbolic

assemblage was associated

and whose values it reproduced in space

(figures 92 and 93). The same fact

is evident in the spiral figures

Australian aborigines draw on sand as

symbolic expressions of the

unfolding of their myths of the lizard or the

honey ant, or in the

carved wooden bowls of the Ainus that give material

expression to the

mythified narration of their sacrifice of the bear

(figure

94).

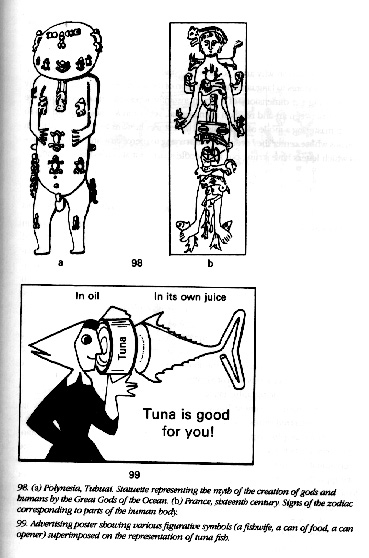

Such a mode of representation is almost

naturally connected with cosmic

symbolism, and we shall consider its

development in chapter 13 in connection

with the humanization of time

and space. This mode has resisted the emergence

of writing, upon

which it exerted considerable influence, in those civilizations

where

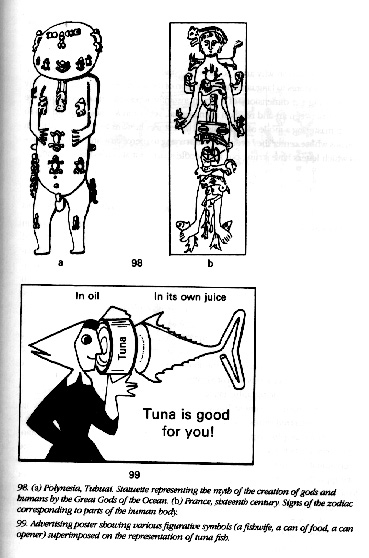

ideography has prevailed over phonetic notation (figures 95 to

97).

It is still alive in areas of thought that came into being in

the early

days of linear written expression, and many religions offer

many examples

of spatial organization of figures symbolizing a

"mythological"

context in the strict ethnological sense

(figure 98). It still prevails

in the sciences, where the

linearization of writing is actually an impediment,

and provides

algebraic equations or formulas in organic chemistry with

the means

of escaping from the constraint of one-dimensionality through

figures

in which phonetization is employed only as a commentary and

the

symbolic assemblage "speaks" for itself. Lastly, it

reappears

in advertising which appeals to deep, infraverbal, states

of mental behavior

(figure 99).

It still prevails

in the sciences, where the

linearization of writing is actually an impediment,

and provides

algebraic equations or formulas in organic chemistry with

the means

of escaping from the constraint of one-dimensionality through

figures

in which phonetization is employed only as a commentary and

the

symbolic assemblage "speaks" for itself. Lastly, it

reappears

in advertising which appeals to deep, infraverbal, states

of mental behavior

(figure 99).

200

Thus the

reason why art is so closely connected with religion is that

graphic

expression restores to language the dimension of the

inexpressible-the

possibility of multiplying the dimensions of a fact

in instantly accessible

visual symbols. The basic link between art

and religion is emotional, yet

not in a vague sense. It has to do

with mastering a mode of expression

that restores humans to their

true place in a cosmos whose center they

occupy without trying to

pierce it by an intellectual process which letters

have strung out in

a needle-sharp, but also needle-thin, line.

Writing

and the Linearization of Symbols

Only agricultural

peoples are known for certain to have had a graphic system

even

remotely identifiable as linear writing.. Eskimos and Plains

Indians,

often cited as examples to the contrary, created

pictographies as a result

of exposure to alphabets. The chief

distinguishing feature of "mythographic"

writing is its

two-dimensional structure which puts it at a remove from

linearly

emitted spoken language. In many nonalphabetic forms of writing,

on

the other hand, the skeleton of the first system of notation is

formed

by survivals from the old multidimensional system of

figurative representation:

This is so for Egypt and China, as well as

for the Mayas and the Aztecs.

One might be tempted to suppose that

these "scripts" had a pictographic

origin, with signs for

concrete objects such as an ox or a walking man

being aligned one

after the other to reproduce the linear thread of language.

Except

for some bookkeeping enumerations in proto-historic China or in

Near

Eastern tablets, there in fact is no known pictographic evidence

of

the origins of writing. From groups of mythographic figures-simple

"rock

paintings" or decorations on objects-we go straight

to linearized

symbols already fully set upon the process of

phonetization.

The pictographic hypothesis presupposes a

"cold" start, an initial

idea of aligning images in such a

way as to match the thread of spoken

language. It would be acceptable

if no other symbolic system had existed

previously, but may prove

false if we apply the "favorable circumstances"

rule and

posit that what took place did not do so all at once but

represented

a transition. Writing did not happen in a void any more

than did agriculture.

The stages that precede both have to be taken

into account. At a certain

moment in time, which was not the same

moment in different parts of the

world, the system of organized

representation of mythical symbols appears

to have combined with the

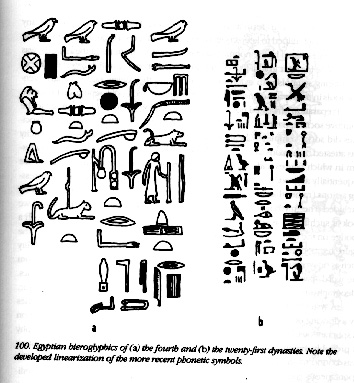

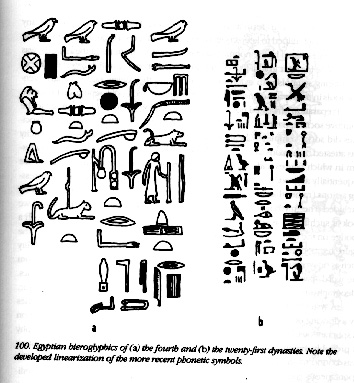

system of elementary bookkeeping (figure 100),

the result being the

primitive Sumerian or Chinese writing in which images

borrowed from

the regular repertory of figurative representation were

drastically

sim-

202

plified and arranged to

form a sequence. The procedure did not yet produce

any actual texts

but helped to keep count of animals or objects. The simplification

of

the figures, necessitated by the nonmonumental, provisional nature

of

the records, was responsible for their gradually becoming detached

from

the initial material context. From being symbols with extensible

implications,

they developed into signs, genuine tools in the service

of memory, on the

one hand, and bookkeeping, on the

other.

Preparation of written bookkeeping or genealogical

accounts is foreign

to the primitive social apparatus. Not until the

consolidation of urbanized

agricultural societies did social

complexity begin to be reflected in documents

whose authenticity was

attested by humans or by gods. Whereas we can conceive

of a

bookkeeping system in which figures and simplified drawings of

animals

or measures of grain are sequentially aligned, it is

difficult to imagine

linearized pictographic signs expressing actions

(rather than objects)

from which the phonetic element has been

entirely excluded. The "mythogram"

in fact is already an

ideogram, as we must realize if we look at such traces

as still

survive today: A cross next to a lance and a reed with a sponge

on

the end of it are enough to convey the idea of the Passion of

Christ.

The figure has nothing to do with phoneticized oral notation

but it has

an extensibility such as no writing can have. It contains

every possibility

of oral exteriorization, from the word

"passion" to the most

complex commentaries on Christian

metaphysics. Ideography in this form

precedes pictography, and all

Paleolithic art is ideographic.

A system in which three

lines are followed by a drawing of an ox or seven

lines by a drawing

of a bag of corn is also readily conceivable. In this

case

phonetization is spontaneous, and reading becomes practically

inevitable.

This form of pictography is probably the only one that

existed at the time

of the birth of writing, and writing was bound to

merge immediately with

this preexisting ideographic system. The

spontaneous confluence of the

two would explain why the earliest

forms of Mediterranean, Far Eastern,

and American writing begin with

numerical or calendar notations and, at

the same time, with notations

of the names of gods or of distinguished

individuals in the form of

figures assembled in small groups after the

fashion of successive

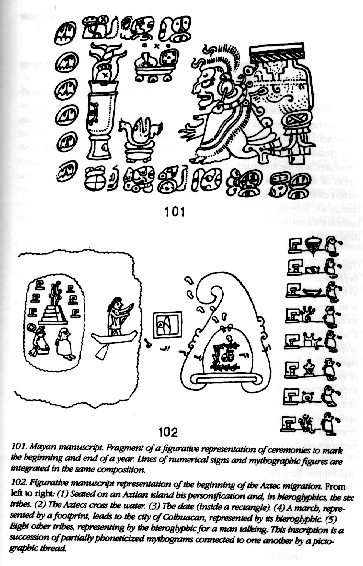

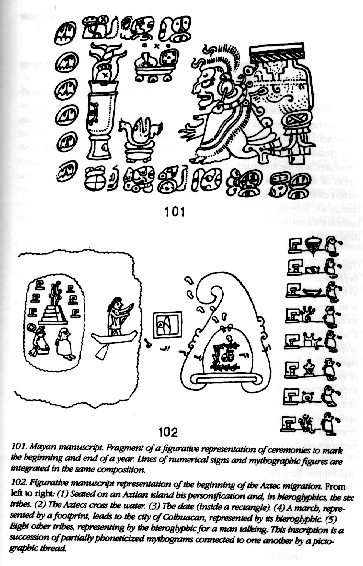

mythograms. We think of Egyptian, Chinese, and Aztec

writing as lines

of phoneticized mythograms rather than as aligned pictograms

(figures

100 to 102). Most recent authors have been well aware of the

difficulty

of fitting the pictographic stage into the development of

phoneticized

writing, but they do not seem to have perceived the

connection between

very early mythographic notation systems, which

implies an ideography without

an oral dimension and a form of writing

whose phonetization apparently

began with numbers and

quantities.

Most recent authors have been well aware of the

difficulty

of fitting the pictographic stage into the development of

phoneticized

writing, but they do not seem to have perceived the

connection between

very early mythographic notation systems, which

implies an ideography without

an oral dimension and a form of writing

whose phonetization apparently

began with numbers and

quantities.

204

Chinese

Writing

For all the variety of known phonetic

scripts, the number of scripts that

developed into fully elaborated

phonetic systems is very limited. Those

of America disappeared before

they had a chance to develop beyond the earliest

stages. The writing

of the Indus has no known descendants. Once the Near

Eastern group of

scripts had been created, there was no further reason,

save very

exceptionally, for any fresh departures, and the languages of

Eurasia

moved directly to syllabic or consonantal scripts or to

alphabets.

Only Egypt and China remained as the two poles of the

ancient civilizations

to develop phoneticized ideographic

systems. Since the seventh century

B.C. Egyptian writing has lost

much of its archaicism, and China alone

has maintained until the

present day a system of graphic symbols that has

more than one

dimension.

The Chinese system combines the two contrasting

aspects of graphic notation

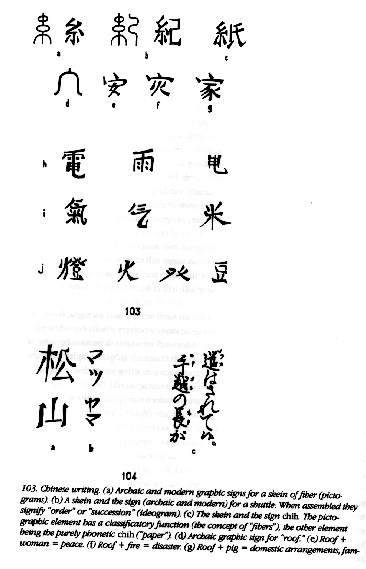

(figure 103). It is a script in the sense

that each character contains

the elements of its phoneticism and

occupies a position in a linear relationship

with other characters so

that sentences can be read easily. The phonetic

reference of the

word, however, is an approximation. In other words, an

ideogram now

used only to represent a sound-a stage that alphabetic languages

too

went through at one time. Chinese as a phonetic tool corresponds

approximately,

though with greater subtlety, to a graphic pun or

rebus whereby the word

"rampage," say, might be rendered by

the signs for "ram"

and "page." Imperfect as it

is, this tool has, because of the

multiplicity of its signs, proved a

satisfactory means of language notation.

We should note, however,

that oral tradition is there to ensure phonetic

continuity: Without

it, Chinese characters would become hopelessly unpronounceable,

even

if recordings of the spoken language were available. Be that as

it

may, Chinese writing in its phonetic role complies with the rule

that governs

all writing by recording sounds in an order that

reconstitutes the flow

of spoken language.

It is a script in the sense

that each character contains

the elements of its phoneticism and

occupies a position in a linear relationship

with other characters so

that sentences can be read easily. The phonetic

reference of the

word, however, is an approximation. In other words, an

ideogram now

used only to represent a sound-a stage that alphabetic languages

too

went through at one time. Chinese as a phonetic tool corresponds

approximately,

though with greater subtlety, to a graphic pun or

rebus whereby the word

"rampage," say, might be rendered by

the signs for "ram"

and "page." Imperfect as it

is, this tool has, because of the

multiplicity of its signs, proved a

satisfactory means of language notation.

We should note, however,

that oral tradition is there to ensure phonetic

continuity: Without

it, Chinese characters would become hopelessly unpronounceable,

even

if recordings of the spoken language were available. Be that as

it

may, Chinese writing in its phonetic role complies with the rule

that governs

all writing by recording sounds in an order that

reconstitutes the flow

of spoken language.

From the

linguistic point of view, Chinese is regarded as word writing,

each

sign representing the sound of a word rather than a letter. This

is

an ambiguous situation because the Chinese word has changed over

the centuries

from being polysyllabic to being monosyllabic, with the

following results:

(1) Chinese literary writing is practically a

series of syllable-words,

difficult to understand without visually or

mentally reading the signs

that correspond to them, and (2) in the

joining together of monosyllables,

the spoken language has

reconstituted a large number of disyllabic or trisyllabic

words so

that the written notation of the spoken language is, in the

final

analysis, a syllabic script. In both of these aspects Chinese

clearly dem-

205

onstrates that writing

was born of the complementary interaction of two

systems:

"mythograms" and phonetic linearization. The

somewhat

strained and often laborious, but ultimately successful,

adaptation of

Chinese writing to phoneticism has resulted in

preserving a particular

form of mythographic notation rather than

simply the remote memory of a

"pictographic"

stage.

The earliest Chinese inscription (twelfth and

eleventh centuries B.C.),

like the first Egyptian inscriptions and

Aztec glyphs, have come to us

in the form of figures assembled in

groups that provide the object or action

they describe with a

"halo" much wider than the narrow meaning

words have

assumed in linear writing. To write the words an

("peace")

or chia ("family") in letters is to

state the two concepts reduced

to their skeleton: To convey the idea

of peace by representing a woman

under a roof opens up perspectives

that are, properly speaking, "mythographic"

in that the

sign is neither a transcription of a sound nor a

pictographic

representation of an action or a quality but an

assemblage of two images

whose interplay reflects the full depth of

their ethnic context. This becomes

still more patently evident when

we see that an assemblage composed of

the signs for "roof"

and "pig" stands for "family,"

a foreshortened

image with the whole technoeconomic structure of ancient

China for

its background.

One might see little difference between

such writing and pictography in

the sense of a succession of drawings

showing actions or objects wholly

outside a phonetic context. Chinese

writing may seem to come close to this

definition because of its

basic principle, which is that one-half of each

character is

"pictographic" and the other phonetic. But to see

in the

Chinese character nothing more than a category indicator (the

radical)

stuck on to a phonetic particle would be an unwarranted

restriction of

its meaning. We need only take a modern example like

the word "flashlight"

to realize how flexible the images

still are (figures 103 and 104). To

the speaker, tien-ch'i-teng means

"flashlight" and nothing else.

But to the attentive reader,

the juxtaposition of the three characters

for "lightning",

"steam," and "lamp" opens

a whole world of

symbols that form a halo round the banal image of the

flashlight:

lightning issuing forth from a rain cloud, for the first;

steam

rising over a pan of rice, for the second; and fire and a

receptacle, or

fire and the action of rising, for the

third. Parasitic images, no doubt,

and likely to cause the reader's

thoughts to stray in a manner irrelevant

to the real object of

notation, worthless images, indeed, in the context

of a modern

object-yet even an example as commonplace as this gives us

an inkling

of a mode of thought based on diffuse multidimensional

configurations

rather than on a system that has gradually imprisoned

language within linear

phoneticism.

207

It is

interesting to note that in a sense the combination of

idiographic

with phonetic notation in ideograms emptied of their

meaning has deepened

the role of mythographic notation in the Chinese

language by deviating

it from its course. It has created a highly

symbolized relationship between

the sound that is noted (auditive

poetic matter) and its notation (a swarm

of images), thus offering

Chinese poetry and calligraphy their superb possibilities.

The rhythm

of the words is counterbalanced by that of the subtly

interrelated

lines, creating images in which each part of each

character, as well as

the relationship of every character to every

other, sparkles with allusive

meaning.

The two

aspect-ideographic and phonetic-of Chinese writing are so

mutually

complementary and, at the same time, so foreign to one

another that each

has engendered separate different notation systems

outside China. The manner

in which Chinese writing was borrowed by

the Japanese is difficult to describe

in terms comprehensible to a

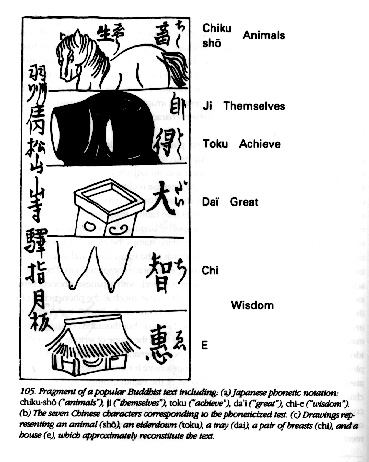

European mentality (figures 104 and 105). The two languages are much

further removed from one another than Latin

is from Arabic, and the

manner in which Chinese writing fits Japanese spoken

language is

something like trying to write French by selecting from among

postage

stamps the picture that approximately corresponds to the meaning

of

the words to be transcribed, and assembling them in rows: Both

grammar

and the phonetic content are completely lost. The characters

were borrowed

at a strictly ideographic level, with Japanese

phoneticism expressed by

signs emptied of their sound in Chinese,

much as the phoneticism of the

figure 3 is different in every

language. Here, however, the borrowing does

not involve a mere ten

signs, as in our numerical system, but thousands

of signs, ultimately

expelling the sound matter of language from the scope

of writing. As

for the ideological matter, it is confined to concepts,

grammatical

inflexions being completely left aside and unaccounted for.

To

compensate for this shortcoming, the Japanese language borrowed

from

the Chinese, in the eighth century A.D., forty eight characters

that are

used exclusively for their phonetic value, and from these it

has created

a syllabic notation register that has inserted itself

between the ideograms.

In consequence, the Chinese system of writing

composed of multidimensional

elements, each group forming a character

contains the means whereby it

can be ren

The two languages are much

further removed from one another than Latin

is from Arabic, and the

manner in which Chinese writing fits Japanese spoken

language is

something like trying to write French by selecting from among

postage

stamps the picture that approximately corresponds to the meaning

of

the words to be transcribed, and assembling them in rows: Both

grammar

and the phonetic content are completely lost. The characters

were borrowed

at a strictly ideographic level, with Japanese

phoneticism expressed by

signs emptied of their sound in Chinese,

much as the phoneticism of the

figure 3 is different in every

language. Here, however, the borrowing does

not involve a mere ten

signs, as in our numerical system, but thousands

of signs, ultimately

expelling the sound matter of language from the scope

of writing. As

for the ideological matter, it is confined to concepts,

grammatical

inflexions being completely left aside and unaccounted for.

To

compensate for this shortcoming, the Japanese language borrowed

from

the Chinese, in the eighth century A.D., forty eight characters

that are

used exclusively for their phonetic value, and from these it

has created

a syllabic notation register that has inserted itself

between the ideograms.

In consequence, the Chinese system of writing

composed of multidimensional

elements, each group forming a character

contains the means whereby it

can be ren

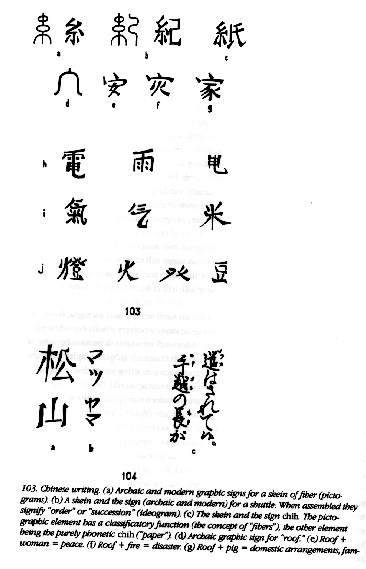

(caption from 103

continued)

ily. (h, i, j) tiench'i ten": electric

bulb. Tien: thunder = rain,

lightning, ch'i steam = cloud, rice;

ten". lamp = fire + mount + pedestal.

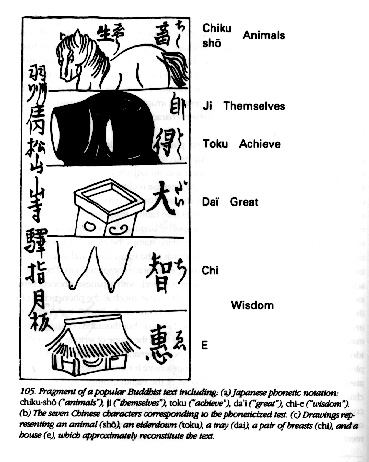

104 Japanese

writing (a) Two Chinese characters: sung-shen, "mountain

of

pines. " (b Japanese reading: matsu-yama, expressed in

syllabic

characters. (c) Fragment of a dramatic text including

Chinese characters

held together by a syntactic "binder" in

cursive syllabic characters

and annotated by phonetic

elements.

209

dered phonetically, Japanese

first stripped the characters of their phonetic

coloring and then

attached a distinctive phonetic sign to each one.

The

Chinese system, like the Japanese, is said to be

"impractical"

and ill-suited for the purpose of translating

spoken language into graphic

terms. This is true only to the extent

that writing is viewed as an economical

method of transcribing narrow

but precise concepts-an object achieved most

efficiently by linear

alignment. The language of science and technology

meets such a

definition, and alphabets meet its requirements. It seems

to me that

other procedures for expressing thought should not be overlooked,

and

in particular those that reflect the flexibility of images, the

halo

of associations, and all the complementary or conflicting

representations

that gravitate round the central point of a

concept. Chinese writing represents

a state of balance unique in

human history: Whatever one may say, it renders

mathematical or

biological concepts faithfully enough, while still preserving

the

possibility of using the oldest system of graphic expression-the

juxtaposing

of symbols to create, not sentences, but meaningful

groups of images.

Linear

Graphism

There is no need here to go into the details

of the history of linear writing.

The Sumero-Accadian scripts, which

before 3000 B.C. already contained a

very large number of ideograms

in process of development toward phonetic

transcription, were

followed by consonantal scripts, of which the Phoenician

(around 1200

B.C.) is the earliest example, and later by the Greek alphabet

of the

eighth century B.C. This continuous development included every

possible

stage-from realistic representation of an object to render

the word for

that object, through the same representation to render

the equivalent sound

in other words according to the principle of the

picture puzzle, through

the process of simplification whereby the

object is made unidentifiable

and becomes a purely phonetic symbol,

to assembling discrete symbols in

order to transcribe sounds through

the association of letters. The development

has been described many

times; it is regarded as the glory of the great

civilizations, and

rightly so for it was this development that put them

in possession of

the means for their ascent.

There indeed is a direct link

between the technoeconomic development of

the Mediterranean and

European group of civilizations and the graphic tool

they

perfected. We saw earlier that the role of the hand in

toolmaking

counterbalanced the role of the facial organs in creating

verbal language;

we also saw that at a certain moment just before the

emergence of homo

sapiens, the hand began to play a

part

210

in creating a graphic mode of

expression that counterbalanced verbal language.

The hand thus became

a creator of images, of symbols not directly dependent

on the

progression of verbal language but really parallel with

it. The

language that, for lack of a better term, E have called

"mythographic"

because the mental associations it arouses

are of an order parallel to

that of verbal myths, both Iying outside

the scope of strict coordinates

in space and time, belongs to this

period. Writing in its earliest phase

preserved a great deal of this

multidimensional vision; it continued to

suggest mental images that,

though not imprecise, were "haloed"

and could point in

several divergent directions. Although our anatomical

evolution had

been overtaken by the evolution of technical means, the

global

evolution of humankind remained perfectly consistent with

itself. The brain

of the man of Cro-Magnon may have been as good as

ours-at any rate, there

is nothing to prove the contrary-but his

means of expressing himself were

far from equal to his neuronal

apparatus. The greatest development has

been in the means of

expression. In primates the actions of the hands are

in balance with

those of the face, and a monkey makes wonderful use of

this

balance. It even goes so far as to make its cheeks serve to

carry

food, which its hands, still required for walking, cannot

do. In early

anthropoids a kind of divorce takes place between the

hand and the face.

Thereafter the one contributes to the search for a

new balance through

gesticulation and tools, the other through

phonation. With the emergence

of graphic figurative representation,

the parallelism is reestablished.

The hand has its language, with a

sight-related form of expression, and

the face has its own, which

relates to hearing. Between the two is the

halo that confers a

special character upon human thought before the invention

of writing

proper: The gesture interprets the word, and the word comments

upon

graphic expression.

At the linear graphism stage that

characterizes writing, the relationship

between the two fields

undergoes yet another development: Written language,

phoneticized and

linear in space, becomes completely subordinated to spoken

language,

which is phonetic and linear in time. The dualism between graphic

and

verbal disappears, and the whole of human linguistic apparatus

becomes

a single instrument for expressing and preserving

thought-which itself

is channeled increasingly toward

reasoning.

The Constriction of

Thought

The transition from mythological to rational

thinking was a very gradual

shift exactly synchronous with the

development of urban concentrations

and of metallurgy. The earliest

beginnings of Mesopotamian writing date

back to about 3500

B.C.,

211

some 2,500 years after the appearance

of the first villages. Two thousand

years later, toward 1500 B.C.,

the first consonantal alphabet appeared

in Phoenicia, toward 750

B.C. alphabets were being used in Greece, and

by 350 B.C. Greek

philosophy was advancing by leaps-and bounds.

Available

evidence of the organization of primitive thought is difficult

to

interpret, either because it comes to us from very fragmentary

prehistoric

evidence or because our records about the thinking of

Australian aborigines

or Bushmen have been filtered by ethnographers

who did not always take

the trouble to analyze them. What we do know

suggests a process wherein

contradictions between different values

are ordered within a participatory

logic that at one time gave rise

to the concept of "pre-logical"

reasoning. Primitive

thought appears to take place within a temporal and

spatial setting

which is continually open to revision (see chapter 13).

The fact that

verbal language is coordinated freely with graphic

figurative

representation is undoubtedly one of the reasons for this

kind of thinking,

whose organization in space and time is different

from ours and implies

the thinking individual's continuing unity with

the environment upon which

his or her thought is

exercised. Discontinuity begins to appear with

agricultural

sedentarization and with early writing. The basis now is

the creation of

a cosmic image pivoted upon the city. The thinking of

agricultural peoples

is organized in both time and space from an

initial point of reference-omphalos-

round which the heavens

gravitate and from which distances are ordered.

The thinking of

pre-alphabetic antiquity was radial, like the body of the

sea urchin

or the starfish. It only just began to master rectilinear

progression

in archaic forms of writing, whose means of expression

were still very

diffuse except for the purposes of account

keeping. The process of the

world's subsequent imprisonment in the

toils of "exact" symbols

had barely begun, and the summit

of perfection in the handling of mythological

thought was reached in

the Mediterranean or in the China of the first millennium

before our

era. It was a time when the vault of heaven and the earth were

joined

together within a network of unlimited connections, a golden age

of

prescientific knowledge to which our memory still seems to hark

back

nostalgically today.

The process set in motion by

settled agriculture contributed, as we have

seen, to putting the

individual more and more firmly in control over the

material

world. This gradual triumph of tools is inseparable from that

of

language-indeed the two phenomena are but one, just as technics

and

society form but one subject. As soon as writing became

exclusively a means

of phonetic recording of speech, language was

placed on the same level

as technics; and the technical efficacy of

language today

212

is proportional to the extent

to which it has rid itself of the halo of

associated images

characteristic of archaic forms of writing.

Writing thus

tends toward the constriction of images, toward a

stricter

linearization of symbols. For classical as well as modern

thinking, the

alphabet is more than just a means of committing to

memory the progressive

acquisitions of the human mind; it is a tool

whereby a mental symbol can

be noted in both word and gesture by a

single process. Such unification

of the process of expression entails

the subordination of graphism to spoken

language. It avoids the

wastefulness of symbols that is still characteristic

of Chinese

writing, and it parallels the process adopted by technics over

the

course of its development.

However, it also entails an

impoverishment of the means of nonrational

expression. If we take the

view that the course humankind has followed

thus far is wholly

favorable to our future-if, in other words, we have

complete

confidence in settled agriculture and all its consequences-then

we

should not view the loss of multidimensional symbolic thought

otherwise

than we do the improvement achieved in the running ability

of Equidae consequent

upon the reduction of the number of their

digits to one. But if, conversely,

we tend to believe that human

potentiality would be more fully realized

if we achieved a balanced

contact with the whole of reality, then we may

ask ourselves whether

the adoption of a regimented form of writing that

opened the way to

the unrestrained development of technical utilitarianism

was not a

step well short of the optimum.

Beyond Writing: The

Audiovisual

With alphabetic writing, a certain level of

personal symbolism is still

preserved. The reconstruction that the

eye performs in reading the written

word is still an individual

one. There is a margin which, though limited,

is indisputably

present, and it ensures a personal interpretation of

phonetic

matter. Moreover the images evoked by reading remain the

property of the

reader's imagination, which may or may not be very

rich. When it replaced

ideographic symbols by letters-when, as it

were, it changed levels-the

alphabet did not abolish all

possibilities of recreation. To put it differently,

alphabetic

writing, while meeting the needs of social memory, still allows

the

individual to reap the benefits of the interpretative effort he

or

she has to make.

We could ask ourselves whether,

despite the current vast increase in the

output of printed matter,

the fate of writing is not already sealed. The

emergence of sound

recording, films, and television in the past half-century

forms part

of a trajectory that

213

began before the

Aurignacian. From the bulls and horses of Lascaux to the

Mesopotamian

markings and the Greek alphabet, representative signs went

from

mythogram to ideogram and from ideogram to letter. Material

civilization

rests upon symbols in which the gap between the sequence

of emitted concepts

and their reproduction has become ever more

narrow. This gap or interval

is narrowed still further by the

recording of thought and its mechanical

reproduction. We might wonder

what the consequences of this narrowing will

be. Curiously enough,

the mechanical recording of images has, in less than

a century,

covered the same ground as the recording of the spoken word

did over

several thousands of years. First, two-dimensional visual

images

became automatically reproducible through photography. Then,

as with writing,

came the turn of the spoken word, reproduced by

means of the phonograph.

Up to that point the mechanism of mental

assimilation had remained undistorted:

Photography, being purely

static and visual, left as much room for freedom

of interpretation as

the bisons of Altamira had left to the humans of the

Paleolithic. The

auditive sequence imposed by the phonograph likewise allowed

room for

personal and free mental vision.

This traditional state of

affairs was not appreciably altered by the arrival

of silent

films. The silent reel was supported by sound ideograms of

an

indeterminate nature supplied by a musical accompaniment that

maintained

a distance between the individual and the image imposed

from the outside.

A radical change occurred, however, with the coming

of sound film and television,

both of which address the faculties of

sight, motion, and hearing at the

same time and so induce the whole

field of perception to participate passively.

The margin for

individual interpretation is drastically reduced because

the symbol

and its contents are almost completely merged into one and

because

the spectator has absolutely no possibility of intervening

actively in

the "real" situation thus recreated. The

spectator's experience

is different from a Neanderthalian's in that

it is purely passive, and

different from a reader's in that it is

totally lived through both sight

and hearing. From this dual point of

view, audiovisual techniques really

seem to represent a new stage of

human development-a stage that has direct

bearing on our most

distinctive possession, that of reflective thought.

From

the social point of view, the audiovisual indisputably represents

a

valuable gain inasmuch as it facilitates the transmission of

precise

information and acts upon the mass of people receiving it in

ways that

immobilize all their means of interpretation. In this

respect language

follows the general evolution of the collective

superorganism and reflects

the increasingly perfect conditioning of

its individual cells. Can a genuine

return by the individual to

earlier stages of figurative representation

still be envisaged?

Writing is unquestionably a most efficient

adaptation

of

214

audiovisual behavior, which

is our fundamental mode of perception, yet

it is also a very

roundabout way of achieving the desired effect. The situation

now

apparently becoming generalized may therefore be said to represent

an

improvement in that it eliminates the effort of

"imagining"

(in the etymological sense). But imagination is

the fundamental property

of intelligence, and a society with a

weakened property of symbol making

would suffer a concomitant loss of

the property of action. In the modern

world the result is a certain

imbalance, or rather a tendency toward the

same phenomenon as that

taking place in the arts and crafts: the phenomenon

of loss of the

exercise of the imagination in vital operating

sequences.

Audiovisual language tends to concentrate image

making entirely in the

minds of a minority of specialists who purvey

a completely figurative substance

to the individual. Image

makers-painters, poets, or technical narrators-have

always, as far

back as in the Paleolithic, been a social exception, but

their work

always remained incomplete because it called for the participation

of

the image users, whatever their cultural levels. Today a

separation

(extremely profitable to the collective) is in process of

being wrought

between a small elite acting as society's digestive

organ and the masses

acting purely as its organs of

assimilation. This development is not confined

to the audiovisual

media, which are merely the end point of a general process

that

involves the whole of human graphic activity. Photography did not

at

first cause any change in the intellectual perception of images;

like

all innovations, it was supported by what already existed. Just

as the

first motor cars were horseless carriages, so the first

photographs were

portraits and scene paintings without color. The

process of "predigestion"

did not begin until the emergence

of cinematography, which completely changed

the concept of

photography and drawing in the purely pictographic sense.

The sports

photograph and the comic strip, together with the

"digest,"

have also contributed to separating the image

maker from the image consumer

within the social

organism.

The impoverishment is not in the themes but in

the loss of personal imaginative

versions. The number of themes in

popular (as indeed in highbrow) literature

has always been limited,

so there is nothing extraordinary about seeing

the same very handsome

and exceptionally strong superman, the same amazingly

attractive

woman, and the same more or less stupid giant appear successively

in

the midst of Sioux Indians and bisons, in a pitched battle during

the

Hundred Years' War, on board a pirate ship, in a police car

roaring off

in pursuit of gangsters, or in a space rocket traveling

between two planets.

Endless repetition of an unchanging stock of

images goes hand in hand with

the tiny amount of free space that the

exercise of emotions related in

one way or another to aggressivity or

sexuality leaves in the indi-

215

vidual

consciousness. That the comic strip's ability to render action in

a

convincing manner is far greater than the old "penny

dreadful's

is not in doubt: In the latter a punch in the face was an

incomplete symbol,

whereas Superman's left hook to the traitor's jaw

leaves nothing to be

added by way of traumatic precision. Everything

assumes a totally naked

reality, to be absorbed without the least

effort, the recipient's brain

perfectly slack.

In this

first part of the book language has been considered on the

same

footing as technics, from an entirely practical point of view

and as a

product of the biological entity called the "human

being." The

initial balance between the two poles of the field

of responsiveness connects

our evolution with that of all animals in

which the performance of operations

is divided between the face and

the forelimb. But by implication it also

connects the existence of

language with that of manual techniques. What

we know about the

evolution of the brain allows us-so far as new techniques

are

concerned-to analyze the connection between erect posture, the

freeing

of the hand, and the opening up of areas of the brain that

were the preconditions

for the exercise of physical abilities, on the

one hand, and the development

of human activity on the other. The

proximity, inside the brain, between

the two manifestations of human

intelligence is so striking that despite

the lack of fossil evidence,

we must accept that human language was from

the very outset different

in nature from the language of animals-that it

was the product of

reflection between the two mirrors of technical gesture

and phonic

symbolism. This hypothesis concerning humans who existed before

Homo

sapiens-humans going as far back as the remotest

Australanthropians-becomes

a certainty when we discover the close

synchronism between the evolution

of techniques and that of

language. The certainty is confirmed when we

see how closely, even

for the very purpose of expressing thought, hand

and voice remain

intimately linked.

Parallel with the extraordinary

acceleration of the development of material

techniques following the

emergence of Homo sapiens, the abstract thought

we find reflected in

paleolithic art implies that language too had reached

a similar

level. Graphic or plastic figurative representation should

therefore

be seen as the means of expression of symbolic thinking of

the myth-making

type, its medium being graphic representation related

to verbal language

but independent from phonetic notation. Although

no fossil records of late

Paleolithic languages have come down to us,

evidence fashioned by the hands

of humans who spoke those languages

clearly suggests that their symbolizing

activities-inconceivable

without language-were on a level with their technical

activities,

which in turn are unimaginable without a verbalized

intellectual

supporting structure.

216

The

parallelism continued at every stage: When agricultural

sedentarization

gave rise to a hierarchical and specialized social

system, a fresh impetus

was imparted simultaneously to technics and

language. If the topographical

structure of the cerebral cortex of

primitive anthropoids accommodated

the joint development of the

material and the verbal, the topographical

structure of the urban

superorganism reflected the same contiguousness.

When the economic

system became transformed into capitalism based on metallurgy

and

grain, the transformation engendered both science and

writing. When

techniques within the city walls began to prepare the

ground for the world

of today, when space and time became organized

within a geometrical network

that captured both the earth and the

heavens, then rationalizing thought

began to overtake mythical

thought. Symbols were linearized and gradually

adapted to the flow of

verbal language until graphic phonetization finally

culminated in the

alphabet. From the beginning of written history, as in

still earlier

times, there has been a complete reciprocal linkage between

technics

and language, and the whole of human development depends upon

this

fact. The expression of thought through language found an

instrument

with infinite possibilities in the use of alphabets, which

totally subordinated

the graphic to the phonetic. All previous forms

remain alive, however,

although to varying degrees. Further on in

this book we shall try to demonstrate

that a significant portion of

our thought diverges from linearized language

in the effort to grasp

that which does not lend itself to strict

notation.

Although the interplay between the two poles of

figurative representation-

between the auditive and the

visual-changed considerably with the adoption

of phonetic scripts,

the individual's capacity to visualize the verbal

and the graphic

remained intact. The present stage is characterized simultaneously

by

the merging together of the auditive and the visual, leading to

the

loss of many possibilities of individual interpretation, and by a

social

separation between the functions of symbol making and of image

receiving.

Here again the parallelism between technics and language

is clearly apparent.

Tools detached themselves from the human hand,

eventually to bring forth

the machine: In this latest stage speech

and sight are undergoing the same

process, thanks to the development

of technics. Language, which had separated

itself from the human

through art and writing, is consummating the final

divorce by

entrusting the intimate functions of phonation and sight to

wax,

film, and magnetic tape.

They have been interpreted as "hunt

tallies," a form of

account keeping, but there is no substantial proof

in the past or

present to support this hypothesis. The only comparison

that might

possibly be drawn is with the Australian churingas, stone or

wood

tablets engraved with abstract designs (spirals, straight lines,

and

clusters of dots) and representing the body of the mystic

ancestor or the

places where the myth unfolds (figure 83). Two

aspects of the churinga

seem relevant to the interpretation of

Paleolithic "hunting tallies":

first, the abstract nature

of the representation, which, as we shall see,

is also characteristic

of the oldest known art, and, second, the fact that

the churinga

concretizes an incantatory recitation and serves as its

supporting

medium, the officiating priest touching the figures with

the tips of his

fingers as he recites the words. Thus the churinga

draws upon two sources

of expression, that of verbal (rhythmic)

motricity and that of graphism

swept along by the same rhythmic

process. Of course my argument is not

that Upper Paleolithic

incisions and Australian churingas are one and the

same thing, but

only that among the possible interpretations, that of a

rhythmic

system of an incantatory or declamatory nature may be

envisaged.

They have been interpreted as "hunt

tallies," a form of

account keeping, but there is no substantial proof

in the past or

present to support this hypothesis. The only comparison

that might

possibly be drawn is with the Australian churingas, stone or

wood

tablets engraved with abstract designs (spirals, straight lines,

and

clusters of dots) and representing the body of the mystic

ancestor or the

places where the myth unfolds (figure 83). Two

aspects of the churinga

seem relevant to the interpretation of

Paleolithic "hunting tallies":

first, the abstract nature

of the representation, which, as we shall see,

is also characteristic

of the oldest known art, and, second, the fact that

the churinga

concretizes an incantatory recitation and serves as its

supporting

medium, the officiating priest touching the figures with

the tips of his

fingers as he recites the words. Thus the churinga

draws upon two sources

of expression, that of verbal (rhythmic)

motricity and that of graphism

swept along by the same rhythmic

process. Of course my argument is not

that Upper Paleolithic

incisions and Australian churingas are one and the

same thing, but

only that among the possible interpretations, that of a

rhythmic

system of an incantatory or declamatory nature may be

envisaged. We see art split away from writing, as it were,

and follow a trajectory

that, starting in abstraction, gradually

establishes conventions of form

and movement and then, at the end of

the curve, achieves realism and eventually

collapses. The development

of the arts in historic times has so often followed

the same course

that we are forced to recognize the existence of a general

tendency

or cycle of maturation-and also to recognize that abstraction

is

indeed the source of graphic expression. The question of the